Salish Ancestral Homeland, St. Mary’s Mission and Fort Owen

One cannot tell the story of Fort Owen without honoring the ancestral homeland of the Bitterroot Salish Tribe. Because of the Salish, St. Mary’s Mission was founded which eventually led to the opening of Fort Owen.

The history of the Bitterroot Valley is rich in Salish Indian culture. For as long as the elders tell their stories, the Salish Indians will know that, from time beyond remembering, this was their homeland, “Spitlemen” meaning the place of the bitterroot. It is a beautiful, rich valley in the shadow of the rugged mountains that loomed far above them like a sheltering wall. This is sacred land, where the spirits of their ancestors dwell, where the earth nourished them, where the animals were their friends. Here, they raised strong energetic horses, greatly admired and coveted by other Indian tribes.

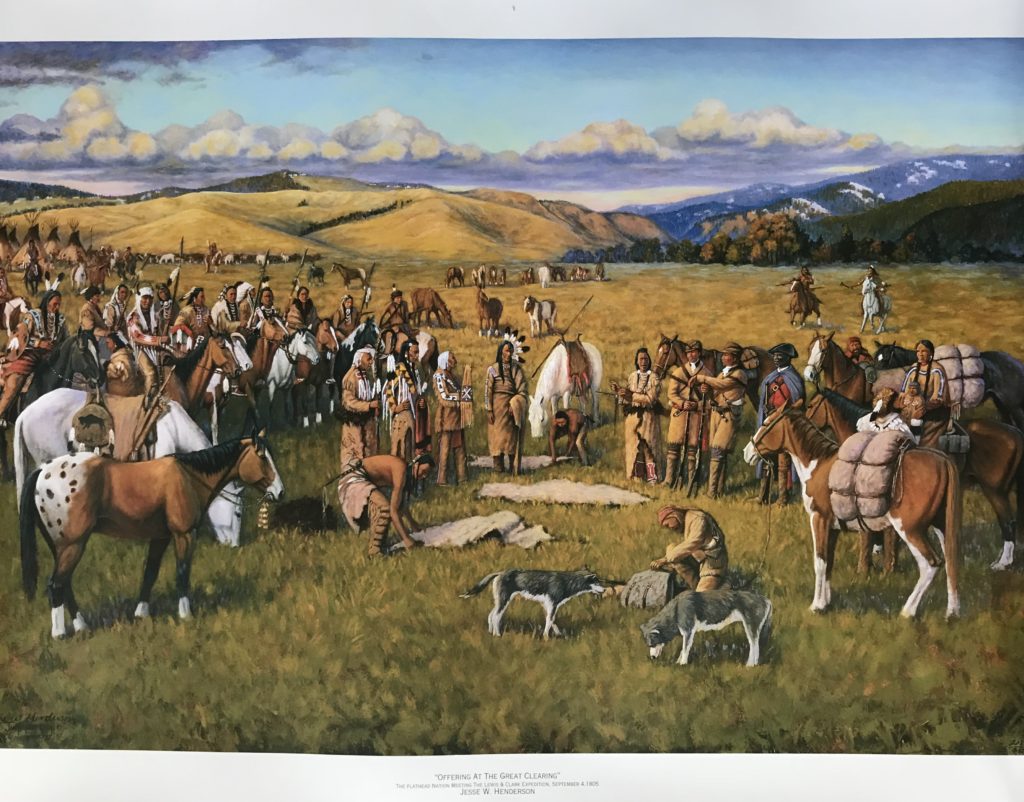

In 1805, Lewis and Clark and the exhausted and hungry members of the Expedition came into the Salish Indian territory. Salish scouts always on the lookout for enemies were both alarmed and intrigued by the group. When the friendly Salish realized these bedraggled travelers meant no harm, they shared their food and welcomed them with gifts and ceremony. The fine Salish horses, which they traded, became lifesavers on the Expedition as it continued its journey over the mountains to the Pacific Ocean.

Before the Lewis and Clark Expedition returned to St. Louis, fur trappers were already invading the streams of the western mountains and valleys, searching for valuable furs that were much in demand. A dozen Iroquois Indians from Canada who were trapping for the Hudson’s Bay Company, found their way onto the Salish lands, settled and intermarried. The Iroquois came from a nation which had been introduced to Christianity some two hundred years earlier. In the light of the campfire the Iroquois told stories of men who wore long black robes, the Jesuit Missionaries, who prayed to the Great Spirit and had good medicine. The Blackrobes buried their dead and spoke of everlasting life. Impressed by this great news, which suited their own faith and beliefs, the Salish Indians and their neighbors, the Nez Perce, were determined to have Blackrobes of their own.

During the decade of 1831-1840 four separate delegations of the Iroquois, Salish and Nez Perce Indians traveled to St. Louis to petition for Blackrobes to live among them. Belgian-born Father Pierre DeSmet, S.J., along with five European missionaries were finally sent in response to the requests.

St. Mary’s Mission was founded on September 24, 1841 which established the first Catholic mission in the Pacific Northwest. St. Mary’s Village was the first pioneer settlement, 48 years before Montana attained statehood.

The first church was built on the east bank of the Bitter Root River and flooded in early spring of 1842. A second log church was built which was soon too small to hold all the faithful. A third St. Mary’s Chapel was built with recycled logs from the first and second structures. The church along with cabins, barns, sheds and mills were built. Montana’s first industries at St. Mary’s Mission included agriculture and irrigation, water-powered grist and saw mills, and animal husbandry. Father Anthony Ravalli, S. J., born in Italy, was Montana’s first medical doctor and skilled architect, builder and craftsman. His artistic and mechanical expertise repeatedly proved valuable on the frontier. Father Ravalli was respected by the Salish people for his gentle and caring ways of teaching and healing. Ravalli County bears his name.

St. Mary’s closed in 1850 because cultural conflicts put the Blackrobes in constant danger. In Montana’s first written conveyance of property, John Owen purchased from the Jesuit Missionaries the mission mills and buildings for $250. Title to the land itself, however, by immemorial occupancy, belonged to the Salish Indians.

John Owen, whose title of “Major” was self-imposed, was a former sutler, or licensed trader carrying goods and supplies for the army. He had come west in 1849 with the army which was to establish posts along the Oregon Trail to protect travelers. Owen, along with his Shoshone wife Nancy and his brother Frank, came into the area at the time the Jesuits were preparing to leave.

The conveyance of property was conditional upon the missionaries return within two years. Included in Owen’s purchase of the mission buildings was the chapel. In keeping with the missionaries’ custom of burning the churches they were forced to abandon, to avoid desecration, Owen carried out the order to burn St. Mary’s Church. By 1852 Fort Owen was established from the nine years of development made by the Blackrobes.

First Irrigation and Water Rights in Montana

The Jesuit Missionaries developed the first irrigation to water their cultivated crops and vegetable gardens. A quote from the Decree of Distribution of the Waters of the Burnt Fork Watershed, Ravalli County, Montana; “First Right, Dated July 1, 1852. This is perhaps the oldest decreed water right for irrigation purposes in the State of Montana. The right is often referred to as the ‘Fort Right’ because the original appropriation of water was made from the lower portion of the Burnt Fork for use upon lands surrounding historic Fort Owen.” The decreed water right is for 507 miners’ inches.

John Owen planted more crops and orchards, purchased additional livestock and developed Father Ravalli’s grist and saw mills into commercial mills. He sold supplies to trappers, military surveyors, Indians, prospectors and traders. Fort Owen became a center of trade and agriculture, plus a community where families and visitors lived, worked and gathered for social interaction.

Fort Owen

Superior of the Rocky Mountain Indian Missions, Father Joseph Giorda, S.J. re-established St. Mary’s Mission in 1866. On October 15, 1866, John Owen recorded in his journal, “The Jesuit Fathers are putting up a chapel near here for the use of the Indians and others who desire to hear divine service.” The fourth St. Mary’s Church was designed and built by Father Ravalli and Brother William Claessens as foreman. The Salish Tribe welcomed the Blackrobes return and assisted with the labor.

Father Giorda visited Fort Owen and John Owen gave him some glass, adobes and other things for the new chapel. On Saturday, October 27, 1866 Owen reported that Father Giorda visited the Fort to invite him to the dedication of the Chapel and he gave Father some candles for the occasion on Sunday, John records, “witnessed the dedication of the New Chapel and the solemn ceremony.”

The proximity of Fort Owen to St. Mary’s Mission provided a social and cultural bond which was, no doubt, pleasing to John Owen and the Missionaries. On a Sunday in July, John walked up to the Mission to take a cup of coffee with Father Ravalli and to discuss, among other subjects, the bear which was killing hogs on Burnt Fork Creek. The next day Father Ravalli sent over to the Fort a dish of green peas and a kettle of new potatoes, first fruits of the Mission garden. Later that summer, Majors Galbraith and Owen dined with Fathers Giorda and Ravalli.

History of Major John Owen

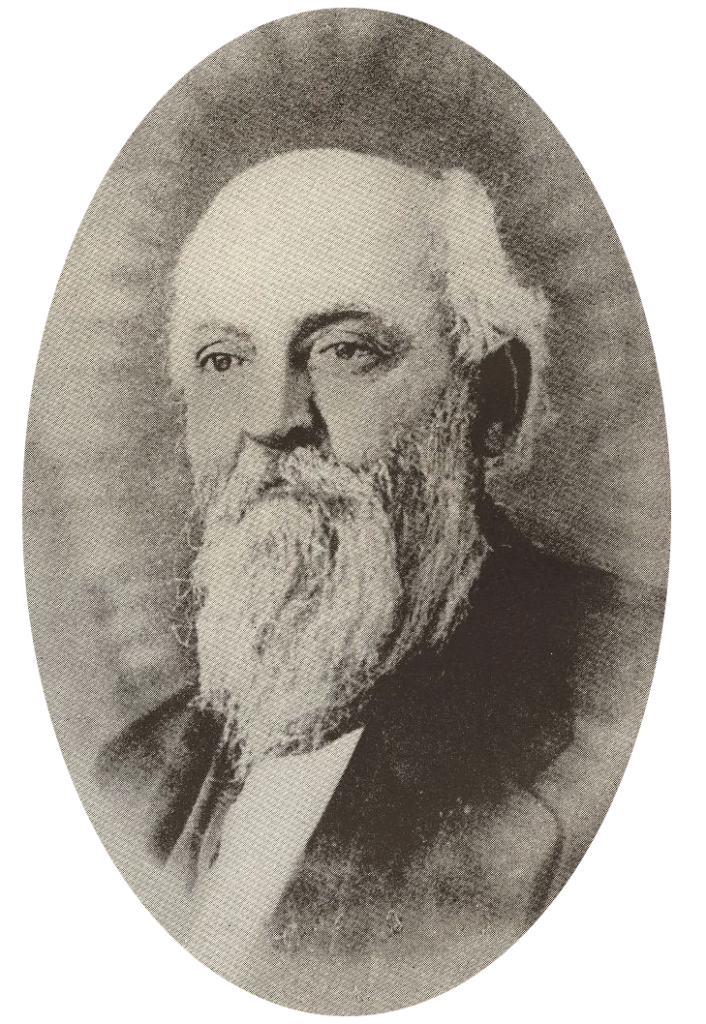

John Owen was born in Pennsylvania on July 27, 1818. His parents, and details of his early life or education are unknown. John is described as being a large man, of medium height, with a fine face, florid complexion, and dark hair, which silvered completely during his years in the Bitterroot Valley of Montana. He had a strong voice, sedate manner, and was described as being a very genial host, and generous neighbor and friend. John was known for his beautiful penmanship and that he was an educated man, as was reflected in his hand-written journals.

MAJOR JOHN OWEN (1818-1889)

From these extensive records, we find that he journeyed west on the Oregon Trail in the year 1849. He was a sutler (licensed military trader) accompanying a regiment of soldiers, who were to establish a string of military posts along the Trail. He spent the winter of 1849-1850 near Fort Hall, Idaho, and met his lifelong companion, and later wife, Nancy. She was a full-blooded Shoshone woman, and an accomplished woodsman, berry gatherer, fisherman and cook. She accompanied Owen and was devoted to him from this time, until her death.

That winter, Owen resigned his position and struck out on his own as an independent trader. He and Nancy made their way to the Bitterroot Valley where John struck up a friendship with the Jesuit missionaries at St. Mary’s Mission. Because of heavy raids on St. Mary’s by the Blackfeet Indians, it was to be shut down. Owen offered to buy the church out of their holdings. On November 5, 1850, when the papers were signed, the first land transaction in Montana occurred, and the first legal document was recorded. For $250.00 John Owen took ownership of 360 acres, and also received transfer of the first water right filed in the state.

Owen named his new purchase Fort Owen. The establishment was not a military fort, but a trading post, and John received his title “Major” not as a military rank, but as the chief trader and owner of the property.

Fort Owen was nearly abandoned in 1853, as Blackfeet raiders were attacking the fort, stealing horses, and killing people. In May of that same year Major Owen, Nancy, and others took their stock, and the trade goods they could, and started for the Pacific Coast. Near Spokane, Washington, they encountered a member of Isaac Steven’s survey team, who was headed to St. Mary’s Village (Stevensville, Montana). This team had soldiers, as well as surveyors, and they were planning to be in the Bitterroot Valley all winter. Owen and his party joined them and returned to Fort Owen, arriving back in August. This action gives Stevensville the claim to being Montana’s oldest continuously inhabited community.

Owen had long term plans for his property and proceeded at once with many improvements. He encouraged the Indians to join him in planting grain, introducing better livestock and finer seed, and planting a fruit orchard. He fostered trading with the Native Americans, fur trappers and emigrants who came through, exchanging furs for goods. He built a lumber mill, and a grist mill which was used for grinding the local grain.

Owen served as Indian agent for six years and did his best to get fair treatment for their people. He requested higher quality livestock, farming equipment, and better seeds, so that the they could enhance their conditions. All they ever received were trinkets, and Owen quit the post in frustration. He studied the Salish language, and prepared a dictionary and phrase book, so he could better communicate.

One very valuable matter John Owen engaged in was to keep continuous and accurate weather reports from 1852 until 1871. His journals reflect a reliable recording of crop reports and a general glimpse into life as it was then.

Owen played host to, and traded with, the companies of soldiers, surveyors, and road builders who passed through the valley. He entertained Governor Stevens, Lieutenant John Mullan, James Garfield, and others. It was said that he was an exceptional host. At his home the table was heaped with the bounties of the area, including fine brandies—some provided by the skills of Father Ravalli.

When John and Nancy were married in 1858, it was one of the first legal unions of a white man to an Indian woman in Western Montana.

From 1851 until 1864, the couple made many pack trip excursions, obtaining trade goods. They traveled over 23,000 miles in those years, from the Bitterroot Valley to The Dalles, Oregon and Fort Hall, Fort Benton, and Fort Colville. It was important that Nancy accompanied John, as he most often needed a navigator. On one occasion, he became lost, tied up his horse, and hiked up on a peak to get oriented. When, he didn’t find his way back to his horse his tracker wife found him and lead the way to their destination.

In 1859, John hired a teacher for the many Indian children he and Nancy fostered. He cancelled those efforts in 1866, when the students ran away to avoid schooling.

On September 24, 1868, John Owen’s world crumbled when his beloved Nancy passed away. He spun into a downward spiral of depression and alcoholism over the next few years. He quit journaling in 1871, and because he neglected his business interests, Fort Owen was foreclosed on in 1872.

Major Owen’s friends tried to help him during this time, but he was unreachable, and in 1874 was declared legally insane. In 1877, friend William Bass took him to his family in Philadelphia, where he remained until his death on July 12, 1889. A portion of his obituary read, “He was brave, generous, of sterling integrity, and many an old pioneer will shed a tear at the news of his death.”

Bibliography:

First Roots: The Story of Stevensville, Montana’s Oldest Community

By The Discovery Writers, 2005.

Published by Stoneydale Press, Stevensville, MT

Montana Genesis

By the Stevensville Historical Society, 1971.

Published by Mountain Press, Missoula, MT

Jesuit Missionaries

Historic St. Mary’s Mission stands in the shadow of St. Mary’s Peak in the Bitterroot Valley of Montana. Fr. Pierre De Smet, a Jesuit priest, founded the Mission in 1841. The State of Montana grew from those early beginnings of the settlement first called St. Mary’s and later named Stevensville. The town holds the distinct honor of being the place “Where Montana Began”. The well-preserved buildings and artifacts of the Mission Complex afford visitors a look back at the historical beginnings of the birth of the State and the settlement of the West.