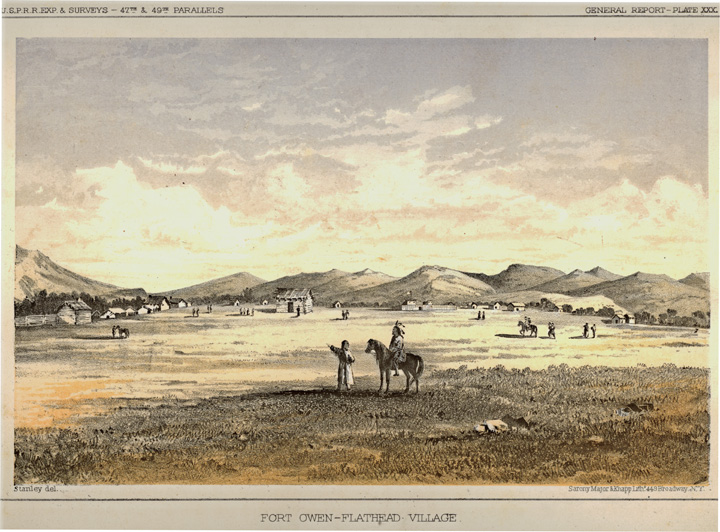

After John Owen purchased the property and a few outbuildings from the Jesuits in 1850, he built his first establishment about ½ mile to the east on slightly higher ground. An 1853 sketch of the original “fort” shows a log stockade containing several log buildings in the vicinity.

Fort Owen’s preservation story begins almost as soon as John Owen decided, in 1857, to rebuild and enhance his first compound, using adobe bricks made from clay ½ mile south of the fort. Why he chose to make the additions out of adobe bricks is a mystery to us today. Fort Owen was a destination for the missionaries and settlers; it was a resting place for travelers, a place to purchase much-needed supplies, or simply a place to visit others in the wilderness. Any one of the people who traveled through this place could have passed on the knowledge of using adobe as a building material. But it was not common practice in Montana Territory in the 1850s. Was it because he felt it was more defendable? Because the amount of wood he needed was a distance away and would require much effort to haul it to the site? Or because it was not as flammable? Or perhaps one of the Italian priests who founded St. Mary’s Mission talked him into it? The journals do not say. They do refer many times to making adobe. There are many references like: “fencing adobe yard,”; “building wall,”; “laying up adobes,” On June 23, 1860, Owen wrote, “About 5,000 adobes made but not dry enough to haul”.

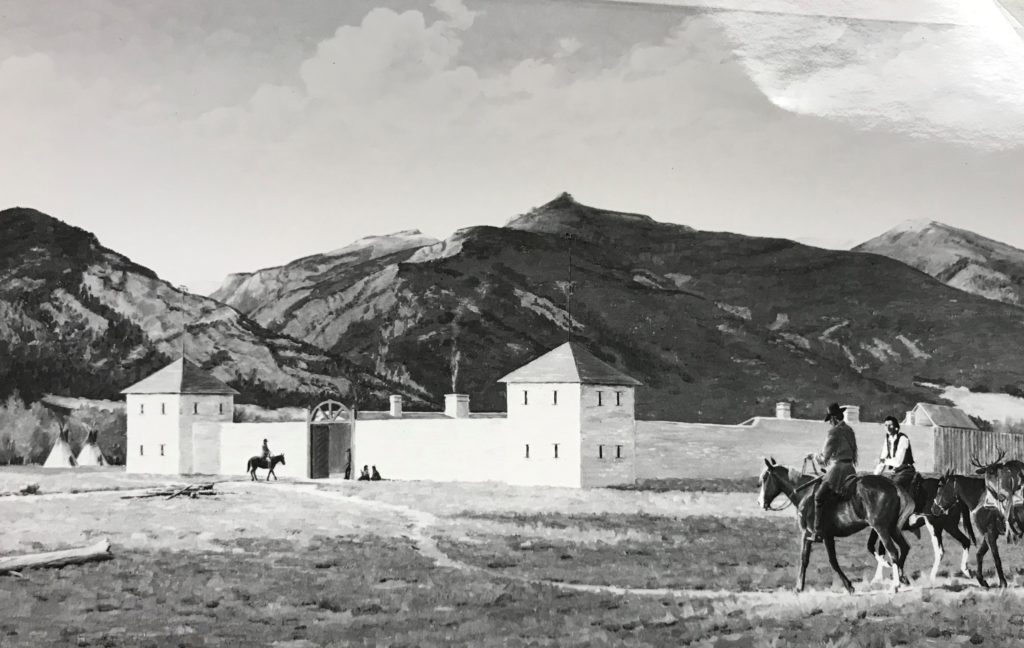

By the time the fort was completed eight years later, they had made and stacked thousands of bricks. In its heyday, it consisted of two main buildings that housed John and Nancy Owens living quarters, a library, a trading room, kitchen, storerooms, a schoolroom; barn; a well house; and a root cellar. There was also an icehouse either in or outside the fort (today, no one knows for sure where it was). The entire fort was enclosed by an eighteen-foot tall and two-foot thick adobe wall with two bastions, twenty-seven inches thick and port holed for musketry, on the southeast and southwest corners. There were entry gates on both the north and south sides. The north gate eventually became the main entryway and was adorned by a large pair of elk horns.

In the 1860s, the fort was a busy regional gathering place and had become quite profitable by providing goods to settlers and gold seekers.

The challenge of maintaining an adobe fort became clear in 1866 when melting snow running down the slope of the north side of the fort caused part of the wall to collapse. References to occasional flooding required constant maintenance.

Late 1800s: The Beginning of the End

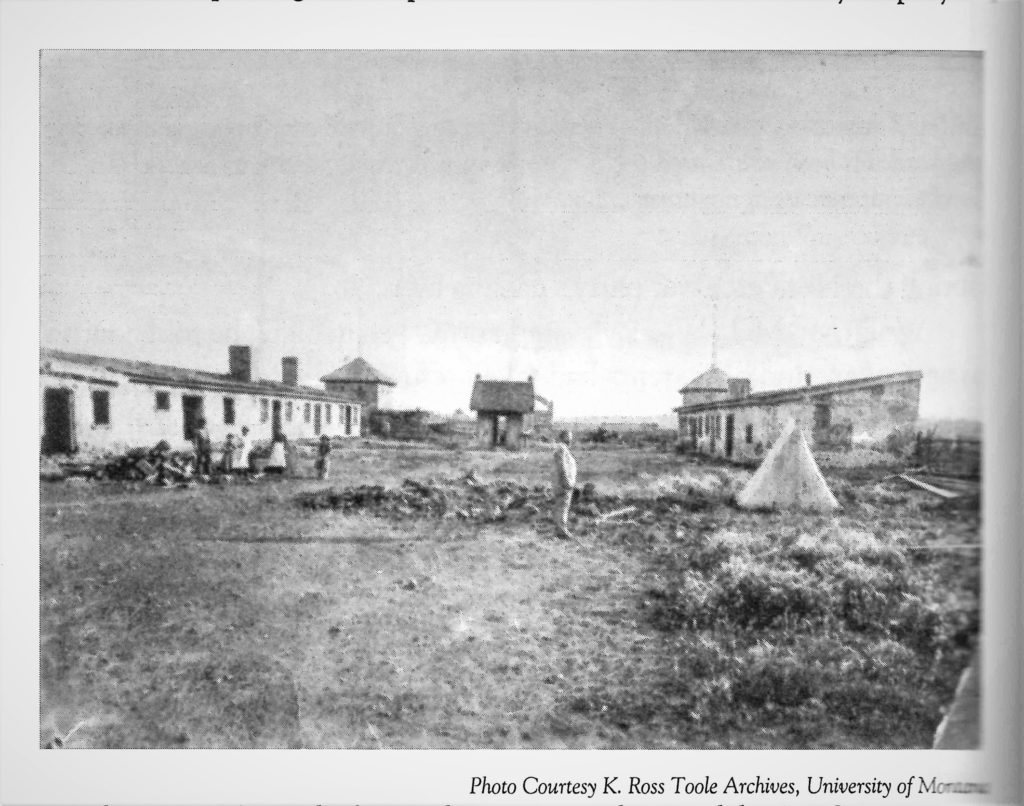

John Owen’s declining mental condition in the early 1870s, as well as the fact the fort had been bypassed by new trade routes, contributed to his financial problems and the declining condition of the fort. John Owen left the fort in 1872. W. J. McCormick, an employee of the fort, purchased the 640 acres of land for $4100 on December 30, 1872, at a sheriff’s sale. A May 12, 1875 article in the Weekly Missoulian described the partial disintegration of the fort: “…portions of the outer walls have yielded to the wear and tear of the elements and lie in broken fragments about the base.”

When the Nez Perce Indians passed through the valley during the Nez Perce War of 1877, a portion of the north end had crumbled down. The settlers, who were afraid of what the Nez Perce might do, gathered and made some temporary repairs by cutting green sod to temporarily build it up again.

The construction of a highway into Stevensville destroyed the north wall and gate in the 1880s. McCormick was killed the same year that John Owen died in 1889, when a violent windstorm blew off the roof of the western barracks while he was on top of it, trying to weigh it down with stones. After McCormick’s death, the land was purchased by the May brothers, who used it as a cattle ranch, with the east barracks being occupied by ranch employees. New ranch buildings replaced the use of the old fort buildings. The other unoccupied buildings soon fell into ruins. In the early 1900s, the bastions were removed, and in 1912, the unoccupied west barracks were leveled.